SAN JOSE, Calif. — Former NASA astronaut Sally K. Ride, a Stanford-educated physicist who used her clout to inspire generations of future women scientists, died on Monday after a 17-month bout with cancer. She was 61.

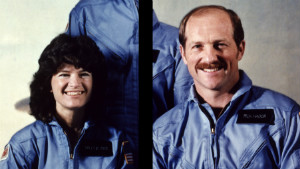

"Sallymania" swept the nation in 1983 when Ride became the first American woman — and then-youngest American astronaut — to rocket into space, manipulating a 50-foot-long robot arm to retrieve a 3,200-pound satellite from aboard the Challenger space shuttle.

Smiling and smart, strong and confident, she was comfortable in a world dominated by crew-cutted men, igniting the imagination of nerdy girls who couldn’t see themselves in the "World and Space" pages of Childcraft encyclopedias.

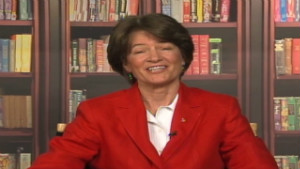

Ride in 2006: Have to 'smash stereotypes'

Ride in 2006: Have to 'smash stereotypes'  Thagard: Sally Ride wanted to inspire

Thagard: Sally Ride wanted to inspire  2008: Ride recounts first space flight

2008: Ride recounts first space flight  1983: Reagan honors Ride & astronauts

1983: Reagan honors Ride & astronauts Once earthbound, Ride dedicated herself to founding San Diego-based Sally Ride Science, an organization that helps create engaging science programs for tweens, especially young girls. She also co-founded the Girls Scouts’ Camp CEO, which introduces minority girls to professional women, and frequently spoke about the importance of strong science education.

"When I was growing up," during the Space Race with the Soviet Union, "it was really cool to be a scientist or engineer," she told a conference at the University of California, Berkeley last year. "We need to make science cool again."

Friends and colleagues were startled and saddened by the unexpected loss of someone who contributed so much. Ride died at her home in La Jolla, Calif., of pancreatic cancer.

"She could have been head of a major aerospace corporation, turning her expertise into a way to make a lot of money," said Joyce Richards, who worked with Ride while leading Girl Scouts of Northern California.

"But that wasn’t her goal," she said. "Her goal was to stimulate girls’ interest in math, science and technology. She was really passionate about the idea that girls need to be taught science in new and different ways — and that girls are more engaged through connectivity, by doing things."

Etta Heber, director of education at Oakland’s Chabot Space and Science Center who shared panel discussions with Ride, called her "a trailblazer, opening doors for countless women. She encouraged girls to dream big, and follow those dreams — their passions."

"Her strength was her ability to work through any political issues or academic issues that interfered with science, technology, engineering and math careers," she said. "She was very clear and direct about fighting the good fight."

Ride was born in Los Angeles, and credited her parents with encouraging her interest in science through chemistry sets and a telescope. She built her academic foundation at Westlake School, a girls’ prep school in Beverly Hills known for its academic excellence.

She was a "fleet-footed 14-year-old with keen blue eyes, a self-confident grin, and long, straight hair that perpetually flopped forward over her face," recalled childhood friend Susan Oakie, later a reporter for The Washington Post.

Ride seemed to enjoy being an enigma, Oakie later wrote. Her favorite songs in high school were Simon and Garfunkel’s ballads about personal isolation. The quotation she chose to head her senior write-up in the Westlake yearbook was, "I do not think, therefore I am a moustache," Jean-Paul Sartre’s parody of Descartes’ "I think, therefore I am."

But then she met a teacher who became her inspiration: Dr. Elizabeth Mommaerts, a sprightly, middle-aged Hungarian woman with a doctorate in human physiology. Mommaerts marked Ride early for a research career.

At Stanford, she earned three degrees in physics — including her doctorate in 1978 — as well as a bachelor’s in English.

She also excelled in sports, ranking nationally as a junior tennis player and joining Stanford’s first women’s rugby team, enjoying its mud-caked, stress-relieving appeal.

She applied for a job at NASA after reading an ad in the Stanford Daily and was named one of the first six women to the astronaut corps. In 1983, she became America’s first woman in space.

At a Johnson Space Center news conference after her historic flight, she dismissed questions about her historic role, saying: "I didn’t come into this program to be the first woman in space. I came in to get a chance to fly in space."

She endured, with good humor, questions ranging from whether she eventually wanted to be a mother to whether she thought women ought to be astronauts. She was asked: Do you cry when things go wrong during flight simulations? Ride, without rancor, replied: "No, I think I respond the same way the men respond."

Ride spent more than 343 hours in space before leaving to work at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Arms Control.

Then she turned to education, her life’s second passion.

Other female astronauts, such as International Space Station crew member and fellow Stanford alum Susan Helms, cited Ride as their inspiration. Helms came to Stanford in 1984 to study engineering — but after hearing a talk by Ride, she knew she wanted to be an astronaut "right then and there."

"I’ve come to realize I will be a role model, even though that’s not what I intended it to be," Ride once said.

"What I intend to do is as good a job as I can — and I hope that will serve as the role model."

———

Visit the San Jose Mercury News (San Jose, Calif.) at www.mercurynews.com

She also excelled in sports, ranking nationally as a junior tennis player and joining Stanford’s first women’s rugby team, enjoying its mud-caked, stress-relieving appeal.

She applied for a job at NASA after reading an ad in the Stanford Daily and was named one of the first six women to the astronaut corps. In 1983, she became America’s first woman in space.

At a Johnson Space Center news conference after her historic flight, she dismissed questions about her historic role, saying: "I didn’t come into this program to be the first woman in space. I came in to get a chance to fly in space."

She endured, with good humor, questions ranging from whether she eventually wanted to be a mother to whether she thought women ought to be astronauts. She was asked: Do you cry when things go wrong during flight simulations? Ride, without rancor, replied: "No, I think I respond the same way the men respond."

Ride spent more than 343 hours in space before leaving to work at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Arms Control.

Then she turned to education, her life’s second passion.

Other female astronauts, such as International Space Station crew member and fellow Stanford alum Susan Helms, cited Ride as their inspiration. Helms came to Stanford in 1984 to study engineering — but after hearing a talk by Ride, she knew she wanted to be an astronaut "right then and there."

"I’ve come to realize I will be a role model, even though that’s not what I intended it to be," Ride once said.

"What I intend to do is as good a job as I can — and I hope that will serve as the role model."

———

Visit the San Jose Mercury News (San Jose, Calif.) at www.mercurynews.com

0 comments:

Post a Comment